Bit Flipping

Bit flipping is another one of those magical attack techniques that a lot of people seem to want to write off as “I think there’s a tool that does that automatically for you.” And yeah I’m sure there’s a bunch. The concept itself seems relatively straight forward. I mean, for the most part a bit can only be in one of two states, so just change a 1 to a 0 or vice versa. And generally that’s what you’re doing in a bit flipping attack. But hopefully I can de-mystify the idea and offer a little more insight as to what you’re doing, as well as hopefully help define the potential for a bit flipping attack in general.

I am categorizing this as crypto since I am going to be bit flipping an actual ciphertext, but it could be argued that this is more or less a web exploitation attack as well.

Giving a Client Control

Let’s play the role of the web developer. I am a developer creating an application that requires authentication to some sort of widget. Can’t let just anyone control the widget, so authentication is required. Now let’s assume that a ton of people need to control the widget, and finally lets assume that a subset of those people need to have more control than others over said widget. So we have:

- A registration page

- A login page

- An authentication page (means to validate the login credentials)

- A widget page, where control of the widget occurs

- An admin page, where admins control the users and other similar tasks

The login page accepts credentials, the authentication page validates credentials, and the widget page and admin page both utilize the credentials to determine if the client has access to the page. But how? Remember that websites are a stateless protocol, meaning the network-level “session” ends when the page stops loading. And on the lowest level, each new request made by the client is a brand new completely unrelated request to the server, and the web server will treat each new request as exactly that: brand new. So how does a web application retain things like authentication between each page request?

Well, one simple method is to require authentication before each request. It’s easiest from the server end, but a nightmare from the user experience end. Nobody likes logging into things! Enter: cookies.

Would you like to view our Cookie Policy?

Cookies are getting kind of a bad rap on the internet. The GDPR has forced any site that uses cookies to disclose their cookie policy just so users have the capability of accessing what kind of cookies they will allow. There’s an unfortunate side of cookies in that many of them serve as tracking mechanisms, allowing servers owned by entities with a vested interest in what you look at to document this information. But the necessary side of cookies can be used for things like session tracking and other similar actions.

Remember that each new page request is essentially a brand new client making a brand new request to the server, and the server has no way (from the network level) to determine your level of access. Cookies are the answer to that. For each request a client makes to the server, the client can also send with them a cookie containing a unique number. The server can take that number, refer to a database which matches that number to a level of access, and now the server knows who you are as well as what level of access you have. It’s that simple!

Except that is a terrible idea. Cookies are stored locally to the client. And therefore, a client should have the ability to modify a cookie at will. Go ahead, try it out! Hit F12 to bring up the Developer Console, and (if you’re using Chrome), go to Application > Storage > Cookies to access all the cookies your browser has stored. From there you can pick whatever field you’d like to modify, make your change and refresh the page. If you’re using Firefox like I am, hit F12, go to Storage > Cookies. Your browser’s developer tools are an incredible toolset to have when investigating websites and what they do.

Alright, so back to authentication. Remember that I’m dealing with a ton of people that would need access to this, so let’s put aside the fact that a cookie can be modified and deal with the fact that for each and every single request going to the server, the server will need to take the resulting number returned from the cookie and perform a database lookup to determine this requester’s access. This is a lot of work for any web server, so most developers simply put such data inside the cookie itself! Imagine if each cookie the client sent to the server simply contained the following data:

1

username=agr0&displayname=Dan&admin=0&otherdata=blah;

The server can simply read the cookie and determine their access. No need to look anything up in a database for each request, it’s right there in the cookie. But how can a cookie be trusted? A user can modify their cookies at will, so what can a server do to trust this data? I mean all I’d need to do is set the value of “admin=0” to “admin=1” and I’d call that a win. What most developers do is they encrypt the cookie somehow and send the [typically base64-encoded] ciphertext as the cookie contents. This way the server holds onto the encryption key. The key would ideally never be exposed, and the client can’t modify the ciphertext simply because the client won’t know how to decrypt it to modify it further. Done and done! This way you can have the clients store their own rights and not have to worry that they will manipulate the data, since they can’t decrypt the ciphertext!

How to Hack This

Well first of all, the quickest win in this scenario is to register a user, then set the display name to something like hahapwnedyou&admin=1; and hope for the best. But let’s assume that the application is smart enough to disallow special characters like & and = in things like the display name or username or something. Now you’re left with a bit of a pickle. You’ve got the ciphertext that you can’t decrypt, and you can’t inject special characters. You’re left with simply modifying the ciphertext if you want to get in. But wait, the cookie is encrypted. Can we modify the ciphertext somehow?

Yes!

Enter: Bit Flipping. The arbitrary manipulation of bytes within a ciphertext to see if the smallest change can actually accomplish something noteworthy. In this case, given the above cookie, it looks like the only thing I will need to manipulate is the second zero, changing admin=1 should suffice, no?

In the essence of bit flipping, this is basically what we’re doing. I’m going to traverse through every single byte in the ciphertext, modify the byte in small increments until I’ve tried every possible combination of 1’s and 0’s in the byte, and see how the server responds.

How does a server respond to pressure?

Now nobody is asking that you DoS the server with a million responses to bring it to its knees. In fact that is the last thing you want to do with a bit flipping attack. You want to generate just as much traffic to be thorough, but not so much as to raise any eyebrows. You are after all sending a bunch of garbage data to the server, and the server will respond in kind. What happens to the application if you send it ciphertext that it can’t decrypt? What happens if it attempts to decrypt it and it’s peppered in some weird control characters? What happens if it tries to decrypt the client cookie and it decrypts to something like this:

1

username=agr0&displayname=D\xfen&admin=0&otherdata=blah;

Well, in most cases you can expect the server to respond with a 500 Internal Server Error, where not even the server knows how to handle your request. In fact the server will most likely dump the traceback into the server logs for the admin to review. So you’ll leave quite a bit of a footprint in the process if you are successful, but believe it or not, a 500 Internal Server Error is a good thing for you, the attacker. This is known as a side channel attack. Where you have a server giving you some indication that either something went wrong (500 error), or something went “ok” (200 OK). You can use this to determine if you’re at least on the right track.

An Example: PicoCTF 2021, “More Cookies”

Given the “More Cookies” challenge, I’m handed a cookie containing Base64-encoded ciphertext, and told that “only the admin can use it.” This is telling me that somewhere in the below ciphertext, the string admin=0 exists. And to that end, without having the ability to decrypt the ciphertext myself, all I’d like to do is change that 0 to a 1. And to accomplish that, first I’ll have to check every single byte, modify it by one, and check to see how the application reacts.

First, some boilerplate header stuff for this challenge:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import requests

import base64

cipher = "alFwUGdQL3hlM0F3YmdOS2FhclZNMjcwZ0pCSkFoUnk3djhPYyt4M05yT2tqV0NBc09KRmRIbFhjWTZjNll5dFQ0MlJUbE1EK1VTa2dpVmVtWmZ6VU1qZ1cxbHgvVC9QUGFXUS9MVXQ5RGRBMzBiZlpFTDBRQ1pqYnowYjVYbUg="

url = "http://mercury.picoctf.net:56136/"

Now the function which actually bit-flips. Given a specific number, a position, and the ciphertext, all this does is add to the byte at the provided position and modulos it by 256 (ensuring we have a valid byte, as >256 would throw an error), then converts it back to a bytestring and base64-encodes it:

1

2

3

4

5

def bitflip(bit, pos, ciphertext):

l = list(base64.b64decode(ciphertext))

flipped = (bit + l[pos])%256

l[pos] = flipped

return base64.b64encode(bytes(l))

The next step here is to simply try every single byte within the ciphertext, try every single possible bit permutation of each byte, and review how the server reacts to each one. In most cases, the server will respond with a 500 server error, but in this particular case, the server is nice enough to respond with a very telling response of “Cannot decode auth_key” or something similar. So that said, using the following code, I can create a possibilities list of bits I flipped at specific positions where the server did not respond with an error message stating that it couldn’t decode the key, and review that for further analysis. This code loops through each bit permutation for each byte in the ciphertext, re-builds the cookie and simply executes a GET request with the new cookie, and tosses out the requests that throw an error:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

possibilities = []

for i in range(256):

for j in range(0, len(base64.b64decode(cipher))):

a = bitflip(i, j, cipher)

cookies = {"auth_name": a.decode() }

r = requests.get(url, cookies=cookies)

if "Cannot decode" not in r.text:

possibilities.append([i, j])

The above code takes quite a bit to run through, as the ciphertext is 128 bytes long (and incidentally, is base64-encoded twice for some bizarre reason, but it shouldn’t really matter considering what I’m doing), and for each byte it iterates 256 times, causing 32,768 requests in total! Needless to say, this is a pretty noisy attack. Hopefully I can get through this without anyone taking notice!

For the record, after this finishes, the possibilities list contains the following number combinations that it ran through the bitflip() function, and the server didn’t return an error message:

1

possibilities = [[0, 0], [0, 1], [0, 2], [0, 3], [0, 4], [0, 5], [0, 6], [0, 7], [0, 8], [0, 9], [0, 10], [0, 11], [0, 12], [0, 13], [0, 14], [0, 15], [0, 16], [0, 17], [0, 18], [0, 19], [0, 20], [0, 21], [0, 22], [0, 23], [0, 24], [0, 25], [0, 26], [0, 27], [0, 28], [0, 29], [0, 30], [0, 31], [0, 32], [0, 33], [0, 34], [0, 35], [0, 36], [0, 37], [0, 38], [0, 39], [0, 40], [0, 41], [0, 42], [0, 43], [0, 44], [0, 45], [0, 46], [0, 47], [0, 48], [0, 49], [0, 50], [0, 51], [0, 52], [0, 53], [0, 54], [0, 55], [0, 56], [0, 57], [0, 58], [0, 59], [0, 60], [0, 61], [0, 62], [0, 63], [0, 64], [0, 65], [0, 66], [0, 67], [0, 68], [0, 69], [0, 70], [0, 71], [0, 72], [0, 73], [0, 74], [0, 75], [0, 76], [0, 77], [0, 78], [0, 79], [0, 80], [0, 81], [0, 82], [0, 83], [0, 84], [0, 85], [0, 86], [0, 87], [0, 88], [0, 89], [0, 90], [0, 91], [0, 92], [0, 93], [0, 94], [0, 95], [0, 96], [0, 97], [0, 98], [0, 99], [0, 100], [0, 101], [0, 102], [0, 103], [0, 104], [0, 105], [0, 106], [0, 107], [0, 108], [0, 109], [0, 110], [0, 111], [0, 112], [0, 113], [0, 114], [0, 115], [0, 116], [0, 117], [0, 118], [0, 119], [0, 120], [0, 121], [0, 122], [0, 123], [0, 124], [0, 125], [0, 126], [0, 127], [16, 13], [28, 15], [31, 15], [35, 15], [194, 11], [218, 13], [227, 11], [234, 11], [234, 13], [237, 11], [241, 11], [242, 11], [243, 11], [244, 11], [245, 11], [246, 11], [247, 11], [248, 11], [248, 12], [249, 11], [255, 12]]

Based on the above, it might be fair to say that the first byte in the ciphertext is a red herring, and doesn’t matter what character it is since it will still decode without a problem, judging by the fact that every single byte is represented here.

The next step from here, once it’s built out its list of possibilities, is to go through each possible iteration and determine which one is the outlier. The best course of action here is to find out the one request size that sticks out the most:

1

2

3

4

5

for i in possibilities:

a = bitflip(i[0], i[1], cipher)

cookies = {"auth_name": a.decode() }

r = requests.get(url, cookies=cookies)

print(f"Headers: {r.headers['Content-Length']}, bit={i[0]}, pos={i[1]}")

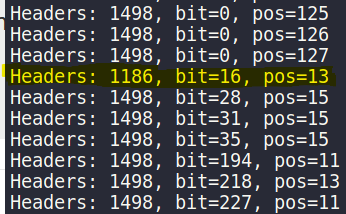

This will print out the response content length for each request we send it, now only limiting it to the contents of the possibilities list. I notice that a majority of requests return the same size bytestring…except for one in particular:

bit=16, pos=13

Plugging these numbers into the bitflip function gives us one in particular:

1

2

3

4

a = bitflip(16, 13, cipher)

cookies = {"auth_name": a.decode()}

r = requests.get(url, cookies=cookies)

print(r.text)

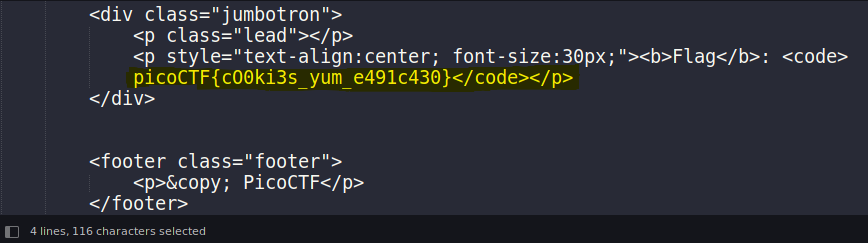

Printing the resulting HTML gives us…

The flag! For all intents and purposes, I have successfully made myself an administrator by manipulating the cookie by changing one single byte. admin now officially equals 1. I didn’t have to decrypt anything, and in fact used a side channel attack to determine if I was on the right track. This was noisy, sure, but to be honest with you…this was easy mode. Sure, situations like this appear in the wild, but granted this is a bit contrived. The cookie was sent to my browser with the string admin=0 already there. It is probably more realistic to assume that if the string admin=1 appears anywhere in the cookie, then the user is an administrator, otherwise the user is not. Simple as that, and probably a bit easier to work with. That said, how can we bit flip something that simply isn’t there? And to top it off, how can we do it without pounding on the server?

This is where we simply inject a little finesse.

CBC Bit Flipping, Hard Mode

Try to stay with me now, this part requires a little bit more logical math.

First, let’s establish some ground rules as stated before. I’m going to work with the following cookie from above, just without the admin=0 part:

1

username=agr0&displayname=Dan&otherdata=blah;

Second, I’m going to say that this cookie is encrypted using AES-128-CBC Encryption, meaning each block of 16 bytes is encrypted with a key, and the resulting ciphertext is XOR’d with the next 16 bytes of plaintext before that gets encrypted. This cipher-block-chain mode continues until it gets to the end, where it finishes with enough padding to extend the plaintext out to be divisible by 16 bytes.

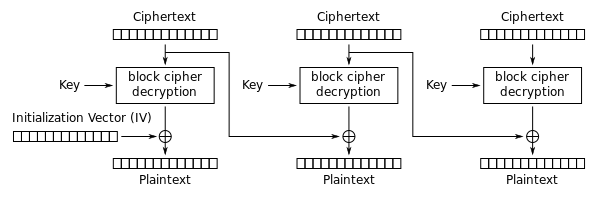

It’s obvious that I can manipulate some of this beforehand, notably the displayname variable. Now the third attribute: to ensure that someone can’t just go ahead and add Dan&admin=1 as their display name, as specified earlier, special characters like & and = will not be allowed in the display name field, or they will at least be escaped. This creates a bit of a barrier, since we can’t just flip a single byte anymore. Now we have to somehow add &admin=1 to the string and bypass the special character filter, but first it’s somewhat important to understand how CBC decryption works.

Here, take note that in CBC Decryption, the ciphertext is split into 16-byte blocks as is expected, and each ciphertext block is used to XOR against the decrypted result of next block. This is important, because we’re going to use this to manipulate the cookie data!

Now to attack, I’ve got to create a payload that works for this particular cookie string. So I’ve come up with the following cookie by manipulating the displayname variable from the application with the following:

1

username=agr0&displayname=Dan,admin,1&otherdata=blah

Mind you, this is only what I assume the cookie looks like. When I change my displyname to Dan,admin,1 I am only presented with this:

1

hkrG5iZbiIDMOh97+n0uHPVqGtLqdhhCpgJ/r/5RUOukzICr21hBzVquTvW89HPs5pW/lI8m2RQeHnyaUQ1uJA==

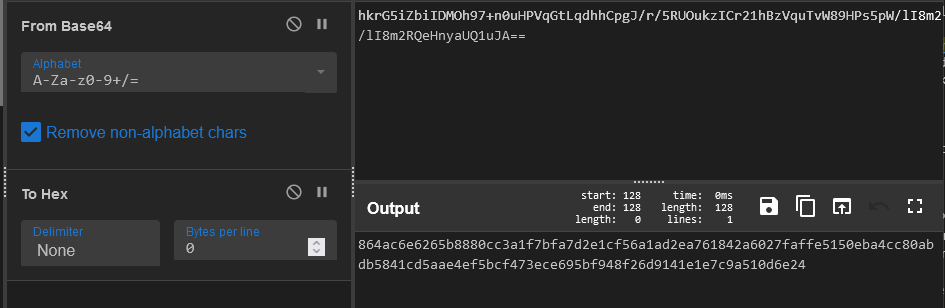

The == sign on the end denotes that this is Base64 encoded, and completely encrypted. I can convert that to something a bit more workable, so using cyberchef I can convert it to hex, which has an easier-to-work-with characteristic of 2 hex characters being equal to one byte:

Now with that, I can deduce the following if I split the above ciphertext by 16 bytes (or technically, 32 hex characters):

1

2

3

4

5

6

Encrypted Ciphertext in Hex ||| Assumed plaintext

======================================================

864ac6e6265b8880cc3a1f7bfa7d2e1c ==> username=agr0&di

f56a1ad2ea761842a6027faffe5150eb ==> splayname=Dan,ad

a4cc80abdb5841cd5aae4ef5bcf473ec ==> min,1&otherdata=

e695bf948f26d9141e1e7c9a510d6e24 ==> blahCCCCCCCCCCCC

To make this easier to work with (and thus manipulate), I will increase the size of my displayname to push the ,admin,1 bit to another block. How about a displayname more like AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA,admin,1? Personally I think it tends to roll off the tongue better than regular old “Dan.”

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Encrypted Ciphertext in Hex ||| Assumed plaintext

======================================================

864ac6e6265b8880cc3a1f7bfa7d2e1c ==> username=agr0&di

f4da7e843d226ce5fc522c02f042104e ==> splayname=AAAAAA

8ebe2590ef24dc7862c6824141f96eb5 ==> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

7387842f0969fbddf0f7e2db1b279961 ==> ,admin,1&otherda

b8ce36acffea4e5402487274bbfca37c ==> ta=blah999999999

Note the 9s on the end to indicate the padding this application created to ensure that the data is divisible by 16. According to the PCKS#7 padding standard, the last block of data should be padded to be divisible by 16 with the number of bytes needed to complete the padding. If the data is divisible by 16 already, an additional block must be created of nothing but characters denoting 16 bytes of padding.

Now, let’s focus on the two lines of the above that are of the most interest to me. Specifically these: (I bracketed the bytes in these blocks that I really care about)

1

2

[8e] be2590ef24dc7862c6824141f96eb5 ==> [A] AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

[73] 87842f0969fbddf0f7e2db1b279961 ==> [,] admin,1&otherda

Remember that in CBC decryption, the ciphertext is XOR’d with the next decrypted block to produce the plaintext. In other words, the first byte 0x8e is XOR’d with something to produce 0x2c, or a literal comma (,). XOR works on a relationship of threes, so we can basically find that “something” out for ourselves:

1

2

3

Remember, all in Hex:

8E ^ 2C = A2

So now we know that the decrypted data before being XOR’d is 0xa2. Okay…so what? Well, again, XOR works on a relationship of threes, so if we know that 0x73 will decrypt to 0xa2 before it gets XOR’d with 0x8e producing the comma, then how can we change 0xa2 to instead XOR to an ampersand (&)? Simple: XOR it with an ampersand!

1

h = hex(0xa2 ^ ord('&'))

In this case, h = 0x84.

So now, if we manipulate the encrypted cookie to change 0x8e instead to 0x84, it should XOR to 0x26, or a literal ampersand (&)!

We can perform the same logic to the following bytes as well:

1

2

8ebe2590ef24 [dc] 7862c6824141f96eb5 ==> AAAAAA [A] AAAAAAAAA

7387842f0969 [fb] ddf0f7e2db1b279961 ==> ,admin [,] 1&otherda

0xdc XOR’d with a literal comma, or ord(',') or 0x2c, equals 0xf0! So if we XOR 0xf0 with the ordinal for an equal sign (ord('=') = 0x3d), we get 0xcd!

So we can rebuild the above ciphertext to the following, where I’ve highlighted my changes, and added question marks because who knows what this will decrypt to:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Encrypted Ciphertext in Hex ||| Assumed plaintext

==============================================================

864ac6e6265b8880cc3a1f7bfa7d2e1c ==> username=agr0&di

f4da7e843d226ce5fc522c02f042104e ==> splayname=AAAAAA

[84] be2590ef24 [cd] 7862c6824141f96eb5 ==> ????????????????

7387842f0969fbddf0f7e2db1b279961 ==> ,admin,1&otherda

b8ce36acffea4e5402487274bbfca37c ==> ta=blah999999999

With a little cyberchef magic, I can check my work…(and ignore the fact that I have the key for this encryption, this is a contrived example after all)

Pwned! Admin=1! And it only took me one request to the server!

Bro, do you even HMAC?

So now that we know how to exploit this, how do we prevent this from happening in the first place? Well, there is definitely more than one way to skin this cat, but my personal favorite is the usage of the HMAC, or Hash-based Message Authentication Code. The extremely high-level idea is you take the entirety of the encrypted cookie, prepend a known key to the beginning of it that only the server knows, hash the result of this new string using something like SHA-256, then hash the result of the hash with the key again. The resulting hash should then be tacked on to the ciphertext in the cookie. Then before working with the cookie in any capacity, you always validate the integrity of the cookie by repeating the process with the given ciphertext (minus the HMAC at the end), and comparing the result with the given HMAC that the client provided for you to determine whether or not the ciphertext was manipulated in transit in any way. If so, cease all further calculation and throw an invalidated ciphertext error. Or even better, fail silently so as to not let the attacker know that they failed the HMAC validation, because there is no reason to give the attacker any more information via side channels.

Final Thoughts

When is encrypted data really encrypted? Sometimes it’s not the key that needs to be protected, but the ciphertext itself. Users should never be trusted to handle their own data, and if it has to be the case, ensure that proper data validation techniques are employed. TRUST BUT VERIFY. Really, this should apply to more than just encryption, but life in general.

Just a thought.