Cracking Easy Crypto

On any given CTF where crypto is involved, I almost always see basically the same challenge every time. You are given a background on how you’ve intercepted the encryption oracle, but not the decryption oracle, along with some ciphertext that you are instructed to decrypt somehow. Usually it goes something like this (and I’m drawing some parallels to a CTF challenge that is currently running right now, so I’m intentionally being vague):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

# You have intercepted the following encryption oracle from the enemy!

def encrypt(msg):

if type(msg) is str:

msg = msg.encode()

res = [((b*963)+2020)%256 for b in msg]

return(bytes(res).hex())

Typically another file or something similar is accompanied with the ciphertext. In this case, the ciphertext is: 05d3d33444401cdf7d44c789c70f4496ba71eb44401cd344d3aed3eb0f0744e01cd3447dd34dbad3404434c77d7d8971ba1044df7d1244ca05d3ae447dd3ae4044ebd3ca. Now do what you do, crypto-guru! Decrypt the code! This is typically marked as an easy challenge, and generally it is on the easier side to figure out, but for people brand new to the crypto game, challenges like this can be somewhat daunting. Like it or not, crypto usually has some form of math, and in this case we have some relatively compressed code involving math that we need to decipher. Before I go about figuring out what to do, let’s break down the code bit by bit.

Breaking Down the Code

Let’s analyze the above code section-by-section.

1

2

3

def encrypt(msg):

if type(msg) is str:

msg = msg.encode()

Some boilerplate stuff. Declare the function, and if the parameter is a string, then encode it to a bytestring. Nothing too fancy here.

1

res = [((b*963)+2020)%256 for b in msg]

This is a bit more involved. Lots of stuff happening on just one line. There’s some math stuff around a list generator. The for b in msg basically means that for every character in the msg variable, assign the character to the variable b and do stuff to it. So let’s break it down by a little Order of Operations magic. Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally!

(b*963)

Multiply the character by 963, and since we’re dealing with a byte string, the “character” is actually just an integer from 0 to 255. So if the character is A, the ordinal of A in UTF-8 is 65. So in this case, 65*963 equals 62595. For simplicity’s sake, I’ll replace (b*963) with (62595).

((62595)+2020)

Now just add 2020 to the result to get 64615. I’ll refer to ((b*963)+2020) as 64615 now:

(64615)%256

Modulo the result by 256, which becomes 103.

Modulo is a pretty fundamental calculation when dealing with crypto. In this case it performs two things: It ensures that the resulting number will be within the range of 0 to 255, as well as makes it extremely difficult to reverse! You’re limiting the range of output, but how can you tell that 103 somehow translates from 65? Well, you know that 65 becomes 103 through this process, but given the ciphertext, how can you take each byte and reverse it back if there’s a modulo calculation involved?

Finally, there’s the return value:

1

return(bytes(res).hex())

It simply take the list, converts it to a bytestring, then converts the whole thing into a printable hex string.

There might be some mathematical way to reverse the output, but I don’t know it (and if I find out how I’ll edit this document). However I do know how to cheat this anyway. Come on along with me!

Analyzing the Ciphertext

The first thing I’m going to do is write the ciphertext to a file for easier use. I created msg.enc and added the hex string there. My goal here is to try and find out what kind of data I’m working with. There is a neat algorithm called the Shannon Diversity Index which determines the entropy of the specified data to build a histogram of the bytes included and give a representation of what kind of data we’re looking at here, even if it’s supposedly “encrypted.” While this is definitely encrypted, it does have a pretty nasty weakness: If you encrypt the same byte over and over again, it will spit out the exact same ciphertext without any difference:

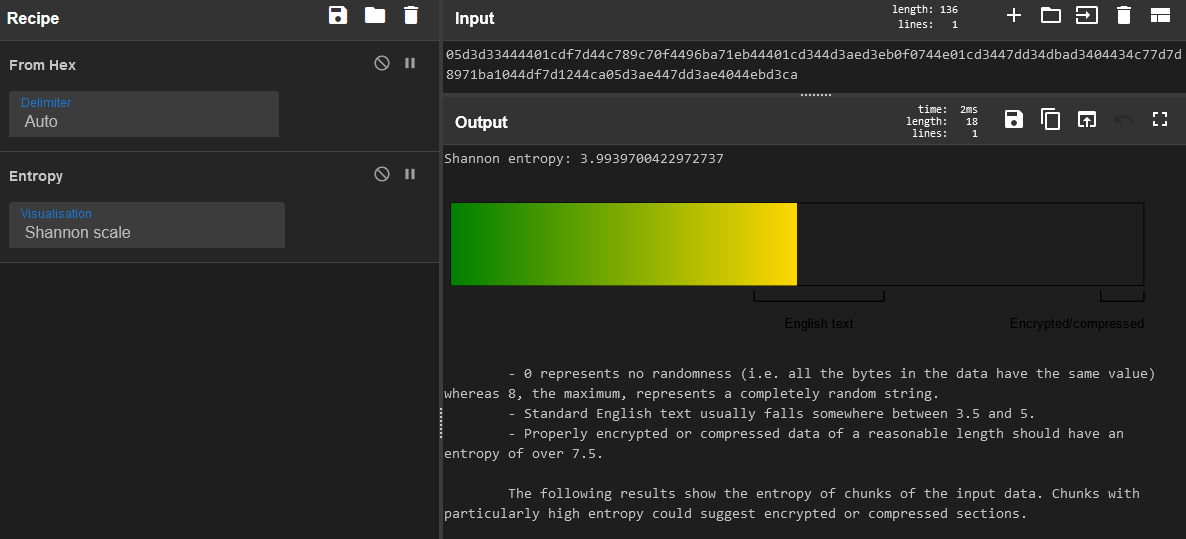

So basically what we’re dealing with is in essence a substitution cipher! Every character in UTF-8 can be represented by another byte. Now there may be a little bit of overlap where two bytes may translate to the same byte, but it hopefully doesn’t happen that often. Regardless, I can run this ciphertext through the Entropy function in Cyberchef to get a feel for what we’re working with (and confirm my suspicion):

And for the sake of being thorough, I can do the same thing using the ent command…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

╭─agr0@agr0hacksstuff ~/Documents/easycrypto

╰─$ cat msg.enc | xxd -r -p | ent

Entropy = 3.993970 bits per byte.

Optimum compression would reduce the size

of this 68 byte file by 50 percent.

Chi square distribution for 68 samples is 1422.82, and randomly

would exceed this value less than 0.01 percent of the times.

Arithmetic mean value of data bytes is 126.3971 (127.5 = random).

Monte Carlo value for Pi is 2.909090909 (error 7.40 percent).

Serial correlation coefficient is -0.138111 (totally uncorrelated = 0.0).

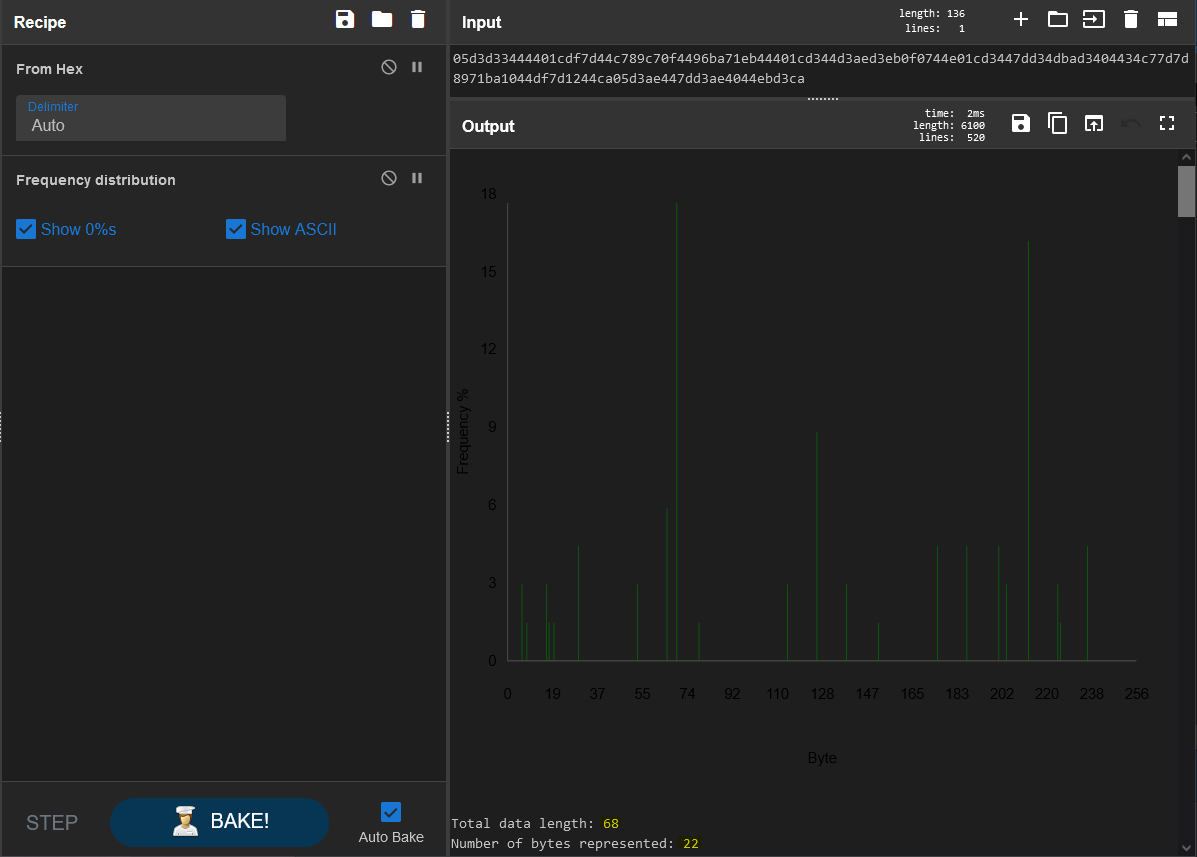

So there we go, the Shannon Index shows this ciphertext as 3.99, where common english falls somewhere between 3.5 and 5. If this byte string were truly random with no patterns to work with, it would fall somewhere above 7.5. It determines this by using the frequency of bytes and where they fall in terms of repetition. The more characters to work with, the more accurrate this will be, but considering there are several bytes re-used we can reasonably determine that this will decrypt to readable text. And for more information, we can use the “Frequency Distribution” recipe from Cyberchef to see the actual re-use of the bytes included:

DARK MODE ALL THE THINGS

Take note of the statistics I highlighted at the bottom there. 68 bytes of data, yet only 22 bytes are represented. Definitely some repetition here. Histograms are a really neat tool for crypto.

So…now what?

Now we know that it’s just a relatively simple substitution cipher. So how do we combat a non-shifting substitution cipher? We create a translation table! Let each encrypted byte equal another and compare the two. We’ll encrypt a charset, then take the resulting ciphertext and map out each byte. Then we simply compare the ciphertext we’re trying to crack with the lookup table we created, and if everything works – boom, we’ll have decrypted it.

First, let’s create a translation table.

1

2

charset = [i for i in range(0, 255)]

encrypted_charset = bytes.fromhex(encrypt(bytes(charset)))

Step 1: create a list of integers ranging from 0 to 255. So: charset[0] = 0, charset[1] = 1, etc

Step 2: Create a variable encrypted_charset where the list is condensed into a bytestring and then encrypted with the same encrypt() function that we have. The fromhex() function is just to handle the hex encoding that the function returns.

1

2

3

translation_table = {}

for i,c in enumerate(encrypted_charset):

translation_table[c] = chr(charset[i])

Step 3: Create an empty dictionary named translation_table.

Step 4: Iterate over each byte in the encrypted_charset list, and assign the byte to the associated byte in the charset list. So now we have a dictionary lookup table. So I can now loop over each byte in the ciphertext and compare it to the translation table. So if the first byte is 0x05, I can find out what that translates to by referencing translation_table[0x05].

1

2

3

4

5

ciphertext = bytes.fromhex('05d3d33444401cdf7d44c789c70f4496ba71eb44401cd344d3aed3eb0f0744e01cd3447dd34dbad3404434c77d7d8971ba1044df7d1244ca05d3ae447dd3ae4044ebd3ca')

res = [translation_table[c] for c in ciphertext]

print(''.join(res))

Step 5: Take the ciphertext and store it as a variable (after we convert it from hex to a bytestring).

Step 6: For every byte in the ciphertext variable, look up the byte against the translation table, and store the result.

Step 7: Using python’s admittedly-stupid join function, print the results of each lookup. The result?

Keep this away from the enemy! The secret password is: "Ken sent me"

Ta-daaaa!

An Alternate Solution

Instead of the translation table, we can go another route: reverse-engineering the encryption function and brute forcing the number required to reverse the output. How do we brute force? Well take what we currently know by analyzing the ciphertext: The result will be human-readable text, and for the record based on other side-channel information leakage, we can also surmise that the text that is encrypted is a specific language (in this case, and for simplicity’s sake, English). So therefore, we can assume that the resulting bytes will all be human-readable. This literally translates to just checking to make sure that all the bytes fall under 127, since the ASCII table only goes up to 127. Beyond that you have your extended ASCII table, featuring weird symbols and stuff not easy to type.

So based on the above, I wrote two functions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

def is_printable(char):

"""

Given a single byte, will determine if it falls within

the printable characters scale

returns: bool

"""

if char > 127:

return False

return True

def all_is_printable(msg):

"""

Checks if all bytes in msg are printable

"""

if type(msg) is str:

msg = msg.encode()

for b in msg:

if is_printable(b):

continue

else:

return False

return True

Two functions which kinda build on top of each other. You have is_printable() which simply takes the character given to it and checks if the ordinal of that character is less than 127, and all_is_printable() which takes a full sentence (or bytestring) and checks if every single byte is printable. If one single byte is not printable it returns False and we can assume that the entire string is not valid. Given that because of the result of the Shannon Index stated that the ciphertext is most likely printable characters, we can assume that this particular check is worthwhile.

That said, now we have a means of brute-forcing. If we can run a bunch of attempts through this all_is_printable() function, then we can technically find out what the key to decrypting is simply by reverse-engineering the function and trying every single number to multiply against.

To this end, we are going to reverse the order of operations. Sally Aunt Dear My Excuse Please.

1

2

3

4

5

def decrypt_attempt(msg, attempt):

if type(msg) is str:

msg = msg.encode()

res = [((b-2020)*attempt)%256 for b in msg]

return(bytes(res))

I created the decrypt_attempt() function which takes two parameters: msg, which is the ciphertext, and attempt, which should be just a number. This will run it through the reverse of the encrypt() function that was provided, which first subtracts 2020 from the ordinal of the character, then multiplies it with the provided number before modulo-ing this with 256.

Now that we have this helper function, I will simply try every single number between 1 and 1000 (to start) and see if I can find any plaintext that contains only printable characters:

I cut out some of the other false positives that resulted in all null bytes, but we got a hit! The index to decrypt is 235! This makes the official decryption function the following:

1

2

3

4

5

def decrypt(msg):

if type(msg) is str:

msg = msg.encode()

res = [((b-2020)*235)%256 for b in msg]

return(bytes(res))

Final Thoughts

An interesting realization I had while writing this: Originally, my encryption function had the following formula:

1

2

3

4

5

def encrypt(msg):

if type(msg) is str:

msg = msg.encode()

res = [((b**3)+2020)%256 for b in msg]

return(bytes(res).hex())

Instead of multiplying it by 963, I’m cubing the character. This actually wound up being not so great, and caused quite a few collisions in the modulo portion of this function, which assigned multiple bytes to the same byte. I’m not sure how to solve something like this as each byte might be completely different and plenty of collisions may result within the modulo portion.

That said, this method of encryption is very, very bad. Don’t do this for production stuff. It may seem relatively confusing and secure, but brute-forcing is definitely a thing that can be used against you here. The standard rule of thumb continues on here: NEVER ROLL YOUR OWN CRYPTO. Seriously, don’t. Unless you are a mathemetician and your crypto has been peer-reviewed and accepted everywhere, your encryption will contain weaknesses that you probably didn’t think about. In this case, this is just a substitution cipher. And while there are ways to make a substitution cipher secure enough, if you’re not doing any shifting in the process then it is probably not going to cut it.

The Moral of the Story

Just stick with AES. And don’t use ECB. Seriously, just don’t use it.