PyNigma, and How I Made It

I’ve said this before through various iterations, but some people work on cars, some build models, I write code to imitate an old cipher device from World War II. While I’ve named this code “PyNigma,” it is perhaps a bit more like Typex considering the amount of rotors used in this process. When I designed this, I didn’t have any sort of intention on inventing something new, this was definitely a hobbyist project. But still, it’s pretty fun to come up with a practical example of what could be considered a “better” way of implementing a substitution cipher. So much better that I even managed to use it to substitute raw bytes.

Regardless, I spent a lot of time getting this together and felt that it was worth writing an article about it. This is how I built PyNigma!

First, How Enigma Works

The basic premise of Enigma is that it is a substitution cipher on steroids. For context on substitution ciphers, perhaps the easiest and most well-known substitution cipher is the Caesar Cipher, where each letter of the alphabet is substituted with it’s pre-determined offset. So an offset of 3 would make A => D, B => E, C => F, etc. It offers little to no security and is generally a means of obfuscation rather than anything else.

To build upon the substitution cipher idea, there exists the Vigenère cipher, which utilizes a key repeated over and over again to determine the offset. If each letter is assigned a number, then the difference between them becomes the offset to tranpose each letter to. So with a key of “APE”:

1

2

3

4

ATTACKATDAWN <-- plaintext

APEAPEAPEAPE <-- Key of "APE"

============

AIXAROAIHALR <-- ciphertext

You can read up on those specific ciphers on Wikipedia, so I won’t go further into them. The basic premise here is substitution ciphers simply transpose one letter to another without any complex bitwise calculations, just standard “This letter = That letter”. This is obviously different from certain things like AES, which shifts and jumbles and XORs and substitutes and all sorts of things.

In a sense, this is all Enigma does. It transposes one letter to another, but does it in varying degrees of psuedo-randomness. One substitution cipher hands it over to another substitution cipher, and it continues down the path until a single key press ends in a lit bulb with an assigned letter, and this letter becomes the ciphertext. What makes it difficult to decipher is that with each key press, one or more rotors turn which changes the substitution cipher on each iteration, and the same letter typed twice would result in two completely separate letters, making it especially difficult to look for common digrams or trigrams like “ee” or “oo” or “ing” or what have you. Bear with me as I go through every single step of the encipherment process.

-

An operator pushes a single key on a typewriter-like interface. For the sake of the argument, let’s say the operator pushes the letter

A. Electronically, this creates a circuit which flows through the entire process, but realistically this circuit can be mapped to letters of the alphabet. -

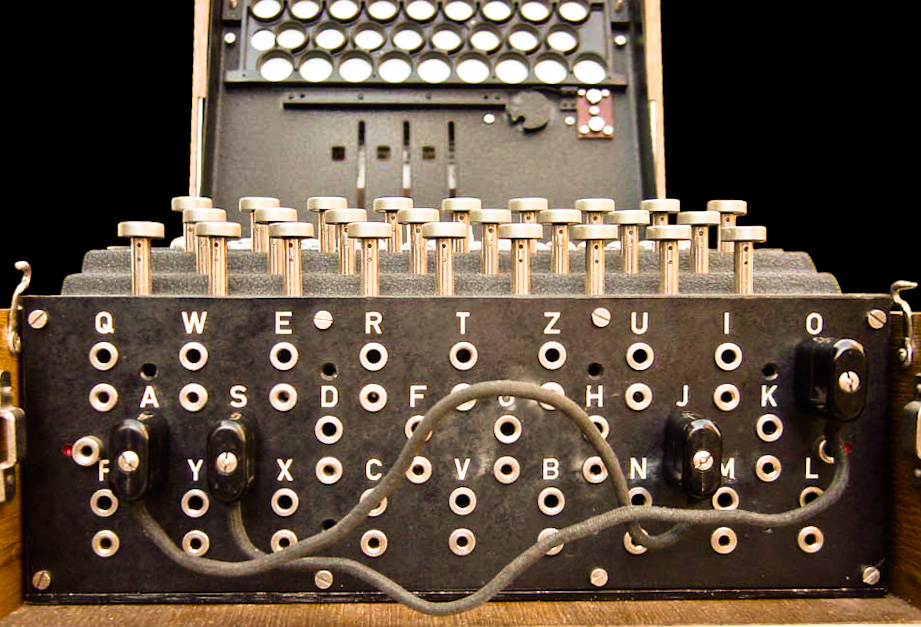

The electricity flows through the first step of the process: The Plugboard. This was located physically on the front of the Enigma machine under the typewriter portion. It was a series of holes that allowed you to insert plugs which simply substituted one letter for another. It looked like this:

If an operator configured A to transpose to J, then it would hand off J to the next step in the process.

-

After the plugboard, the circuit continued up through the set of rotors. Each rotor was its own set of substitution ciphers, mapping each letter to another letter altogether. Rotor 1 would change the input letter of

JtoEas an example, and it would hand off to Rotor 2. This would transposeEtoU, then hand off to rotor 3, which would transposeUtoY. The key point here is that at each key press, rotor 1 would turn once and become a completely different substitution cipher! Even worse is if rotor 1 performed a full cycle, it would automatically rotate rotor 2 by one increment, changing that rotor into a completely different substitution cipher. And finally, if rotor 2 performed a full cycle, it would rotate rotor 3 by one increment as well, changing that into a different substitution cipher as well. On later versions of Enigma, more rotors would be added to the mix to make it even harder to crack. -

To make matters worse, for reasons that will become clear in a bit, a reflector circuit was then hit, which would physically direct the current through a final static transposition cipher (in this example, mapping

YtoB), and then back through the rotors in reverse order. Rotor 3, then 2, then 1, substituting along the way.Bgoes toN,NtoW, andWtoR. -

Finally after redirecting through rotor 1, the current would flow back to the plugboard where it receives a final transposition,

RtoC. -

A bulb on the lamp panel would light up corresponding to the letter

C. This was then written down as the ciphertext and transmitted over the air.

If an operative received the encoded text and they knew the enigma settings that created the ciphertext, they would set the rotors to the same setting as put in for original message, and simply type the ciphertext in the same way to reveal the plaintext. This is one of the reasons why Enigma was so well received: There was no additional bulkiness for an encrypt and decrypt function, if you knew ahead of time what the rotor and plugboard settings were, you could simply type in the ciphertext and it would give you the plaintext.

Of course, this meant that Enigma had to be reflective. If A equals C, then C had to equal A. Unfortunately this phenomenon proved to be a significant weakness to Enigma, because due to the reflective nature of it, you could press A a billion times and the ciphertext will never print out an A as well. This small hint was integral in breaking the Enigma Cipher thanks to the hard work of the Polish and Alan Turing as well.

Why did I do it?

I don’t know, it seemed kinda fun. How can I take the basic idea of Enigma and make it better? Are substitution ciphers actually viable? And moreover, can this be applied to raw bytes as well? I can answer the last one definitively: Yes.

PyNigma

I messed around with this for about a week until I got to a point where not only could I utilize the basic concept of Enigma with ciphertext, but I could also generate a key (aka the Enigma Settings) and encrypt a file with it byte-by-byte. The general usage is outlined in the Github repository I linked, but I’d like to go over the code flow.

General Note: Random Numbers Ahoy

At the time of this writing, pynigma was created with the usage of python’s random library, and not the secrets library. This flies in the face of a previous article I wrote regarding how not-random PRNG’s are, and this is no different. However, the random library had several functions that secrets did not have, so I used that strictly out of laziness. To fix this, I could load up the secrets library and generate a seed for the random library, which should be perfectly cryptographically random enough. And that would be a simple fix. But again, it’s lazy, and frankly I don’t even think you should use this to encrypt sensitive things anyway since it was based on a formula that was cracked about nearly a century ago. So use this with caution! …or if you’re feeling particularly useful, feel free to contribute code to make the PRNG better. Would love to see it!

Anyway, back to PyNigma…

First, Generate the Rotors

Generating a rotor is twofold: First, you create the actual transposition table, which is typically randomly generated. This is stored as a dictionary in python, where transposition_table['a'] = 'b' and so on. Once the dictionary is created, then create the actual Rotor object and give it the created transposition table, as well as the start and shift values, which refer to the initial value the rotor should start on and the amount of times the transposition table is rotated per iteration, respectively.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

import enigma

import random

# First, create a shuffled version of the character set as a list

r = [c for c in enigma.charset]

random.shuffle(r)

# Now split the list in two halves

left = [c for c in r[:int(len(r)/2)]]

right = [c for c in r[int(len(r)/2):]]

# Lay them on top of each other, then build a transposition table

# where each value equals the other, making it reflective!

transpose_table = {}

for i,j in zip(left, right):

transpose_table[i], transpose_table[j] = j, i

# Assert reflective nature

test = transpose_table[transpose_table['a']]

assert 'a' == test

Now with that, I can use the new trasnpose_table variable to simply map one character to another. The next step here is to find out a way to “rotate” the transpose table. Code incoming!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# Build a list from the keys of the transpose_table. This preserves

# the order of the current transpose table.

r = [transpose_table[k] for k in transpose_table]

# Shift the list over by one

r = r[1:] + r[:1]

# Now rebuild the transpose_table dictionary like I did before

left = [c for c in r[:int(len(r)/2)]]

right = [c for c in r[int(len(r)/2):]]

transpose_table = {}

for i,j in zip(left, right):

tranpose_table[i], transpose_table[j] = j, i

Now we have a means of “rotating” the rotor. Neat! I only shifted it by one, but you can change that to whatever value you’d want, and even make it more user-friendly by using the modulo of the length of the r variable so you can put in a dumb shift value of something like 10,000,000 and it will still work without throwing an “index out of bounds” error.

The concept of the “Rotor” makes a good use case for a Python Class, considering I will need to keep track of things like the current state of the rotor as well as the particular rotor’s transposition table, so I can convert it to that without a problem. But adding it as a class also allows me to add yet another interesting property: The capability of defining the next rotor in sequence! If I have the ability to rotate the next rotor in the sequence, I can create a chain of rotors that know enough to rotate the next rotor after it’s completed a full cycle. I can simply create a new variable in the __init__() function of the rotor object which will serve as placeholder for the next rotor in the sequence. If it performs a full cycle, it then calls the next rotor’s rotate() function. If it doesn’t, it calls the next rotor’s transpose() function, and if there are no rotors next in the sequence, simply return the transposed value of the character we are substituting, and it will cascade back down the rotor chain.

Second, Generate the Plugboard

This was a lot simpler than creating a rotor object since there are literally no moving parts to the plugboard and it’s simply a static substitution cipher, but it can also take in a configuration of plug settings. This meant that it needed an input with special characters to denote what characters should transpose to. My goal was to create a static transposition cipher – which is simple enough – but to also allow for a configuration input. I settled on a syntax I called plugformat, and it looked like this: A-C|B-K|3-5, and it would be read in such that A would be transposed to C and vice versa, B would transpose to K as K would also transpose to B, etc. So hypens would be flanked by two characters, and pipes would be the delimiter between directives.

Unfortunately this had the side effect of forcing me to not include hypens and pipes into the character set, because otherwise this would get very confusing to work with. Now I’m sure I could probably use a different delimiter besides a hyphen and a pipe, but I wasn’t thinking straight and frankly it wouldn’t really matter in the direction I would ultimately head in. More on that later.

Also, I’m sure I can use a format similar to the enigma plugboard settings like AC BK 35 but I added literal spaces to the character set, and also for this whole thing to work the character set needed to be a length divisible by 2, that way every single character can be substituted with another unique character and back.

The code for generating a plugboard substitution cipher was:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

charset = 'abcd...' # etc etc

def build_plugboard(plugformat):

transpose_table = {}

if plugformat is None:

# No substitution, call it a day.

for c in charset:

transpose_table[c] = c

else:

try:

for inst in plugformat.split('|'):

if len(inst) == 3:

i_from, i_to = inst.split('-')

if i_from in transpose_table or i_to in transpose_table:

# We have overlap!

raise Exception("Overlap in plugboard format!")

transpose_table[i_from] = i_to

transpose_table[i_to] = i_from

except ValueError:

raise Exception("Please follow plugformat of a-b|c-d|d-e")

finally:

for c in charset:

if c not in transpose_table:

transpose_table[c] = c

return transpose_table

In the above case, it simply returns the transpose table, but like the Rotors, this is better used as a class object.

Create the Key

Now that I have the rotors and plugboard objects defined, all I need to do is create a larger object that builds a working machine using a pre-defined configuration. This configuration should be considered the key! So before I go about creating the engine, I need a function that creates a key. You can be particularly granular if you’d like and define the amount of rotors and shift values and all that along with the plugboard, but since that can be time consuming and frankly kind of ridiculous, I need to create a function that does it all for you. I needed to create the generate_key() function.

What I figured I would do is to create a configuration that can be read in easily, and provide everything that the enigma cipher needs to do it’s thing. Now as to exactly what that means, I came up with the following structure:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

{

plugboard: <plugformat applied to plugboard>

rotors: [

0: {

start: <starting pos of rotor>

shift: <shift value of rotor>

rotor: {

<base64-encoded and zlib compressed rotor substitution dict>

}

checksum: <sha256 hash of rotor>

}

1: {

etc etc etc

}

]

}

As I write this I realize that the checksum portion is probably not necessary, as it either works or it doesn’t – but at least this has some form of error checking, albeit a weak one. Whatever.

Now what I can describe from this particular structure is the fact that not only am I storing the plug format, the shift values and starting positions of each rotor, but the specific transposition table of each and every rotor as well! What winds up happening is that if I have a particularly complex enigma cipher, this key grows to an astromonical size. Without compression and simple base64 encoding came to 16 Kilobytes long! That’s a tremendous size. With the addition of zlib compression as much as I could, I dropped this size to around 4 Kilobytes thankfully, so at least I had something to work with.

Now, with the key format in place, I could create a function which randomly generates a key. Without going into it, you can view the source code to the generate_key() function in the github repo. Of course, now that I can generate a key that’s zlib compressed, json-formatted and base64 encoded, I can also create a read_key() function which basically unpacks the object into a python object that can be used to generate the cipher.

Tying it All Together

So I have the key generator function, the Rotor class object and the Plugboard class object, now I just need the all-encompasing Enigma class to regenerate the cipher based on the key that is passed to it. Luckily this is probably one of the simpler class objects to write, since most of the hard work is already done.

Behold, the Enigma class object!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

charset = '0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRS' \

'TUVWXYZ !@#$%^&*()\'",./:;'

class Enigma:

def __init__(self, key):

"""

Takes the enigma key defined in keyformat which has been deciphered

and broken down using the read_key() function, which returns a complex

python object. This object will then be used to create the enigma

machine used to encrypt (and decrypt!) plaintext.

"""

self.key = read_key(key)

self.rotors = []

first = True

for r in self.key["rotors"]:

if first:

self.rotors.append(Rotor(tpose=r['rotor'],

start=r['start'], shift=r['shift']))

first = False

else:

self.rotors.append(Rotor(tpose=r['rotor'], start=r['start'],

shift=r['shift'], r=self.rotors[-1]))

# Build the plugboard

self.plugboard = PlugBoard(plugformat=self.key['plugboard'])

self.charset = charset

Taking in a key from the generate_key() function, it simply unpacks everything using the read_key() function into a dictionary object, and applies the items within that dictionary to generate the Rotors and Plugboard. Now that the settings are there, I need a way to encipher some text:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

# Continued from above

def transpose(self, data):

"""

Does the actual transposition of each individual letter.

"""

res = ''

for c in data:

if c in self.charset:

r = self.plugboard.transpose(c)

r = self.rotors[-1].rotate(r)

r = self.plugboard.transpose(r)

res += r

else:

res += c

return res

Takes in a string, and iterates over each character in the string. If the character in question is a member of the supplied charset, it first transposes from the plugboard, takes the result of that and passes it through the Rotor chain and back again, then through the plugboard yet again. It returns the result.

The beauty and elegance of this is that if you create another Enigma object using the same key and pass in the ciphertext provided, it should decrypt back to the original plaintext! No need for a separate decrypt function!

What Else Can Be Done?

So right now I’m using characters from an 80-byte character set. This is somewhat limiting, especially since hyphens and pipes cannot be represented. But if I can do it with 80 characters, I should be able to do it with 256 characters, no? It’s an even number, and if so I can properly represent every single bit configuration in a byte and transpose by that, so therefore I should be able to apply this not only to strings, but raw bytes. The trick here is getting python to work with bytes instead of strings, and the basic idea there is generally that bytes are represented as numbers…except when they’re not. The transpose table is still working the same way, where a dictionary will map something like transpose_table[b'\x9a'] = b'\x42' and what have you, but I just had to take care to ensure that strings were converted to bytes if possible and the resulting encoding necessary from doing that. Ultimately I came up with subcrypt.py, short for “substitution crypto” which accepts binary data as input and tranposes accordingly.

Used in conjunction with en.py, the command line encoding tool which I made begrudgingly with the help of the argparse library, you can now encode binary data!

With the help of century-old engineering, I applied a complex substitution cipher to what could potentially be decent encryption. I’m pretty proud of it.

Final Thoughts

Now this begs the question of “Is this decent encryption?” Meh, probably not. I figured a list of pros and cons might be beneficial for this cipher:

Pros

- Symmetric Encryption. One key to rule them all.

- The key contains the transposition table of each rotor. This means that without this table there is no way (that I know of) to determine the relation of one character to its transposed value.

- No bitwise calculation performed, all substitution ciphers. Not very complex on the lowest level so it’s easy to understand its concept, but extremely difficult to reverse engineer a ciphertext.

- No need for a separate decrypt function as this is a reflective cipher.

Cons

- Symmetric Encryption. You would need to share the key with the intended party somehow in a separate secure channel. Most likely through the use of a Diffie-Hellman key exchange and RSA…but at that point, just use RSA.

- S L O W. This cipher takes a looooong time to run. Using the default of 5-10 rotors and a plugboard of a max of 20 possible settings, this took me about 74 seconds to encrypt a 1 Mb file of only zeroes. This can potentially be sped up with a more low-level language like C or even Go, but since I did this as a means of a proof of concept I chose python. Perhaps I can get some speed from this if I incorporate Cython? Could be worth revisiting.

- Like the original Enigma, this cipher is plagued with the same issue of never encoding one character to the same character as the plaintext. Meaning if you use a plaintext of the letter

Aa billion times, the resulting ciphertext will never output a letterA. This was one of the biggest vulnerabilities the original Enigma had that the Allies exploited. Perhaps this may tell you too much about the plaintext, but hopefully with a character set of 256 instead of the original 26 this vulnerability won’t be as potent.

Additional Things of Note

- I can probably optimize this a bit. Is there a need for a plugboard? Can’t I just use the Rotors?

- How many rotors are necessary for Good Enough Security TM?

- Just use AES.

Parting Words, and a Potential Use-Case?

It’s difficult to explain my way of thinking when creating an encryption algorithm. Especially one that only substitutes bytes. AES does that and a lot more, and it does it really well. That said, I could potentially implement a stream cipher with this mechanism as well. Simply design a keystream using a bytestring repeated over and over again as the plaintext, then XOR the keystream with the plaintext to produce new ciphertext. In a sense, it would be like a jacked-up version of the Vigenère Cipher. Say the keystream was just the word APE repeated over and over again, plugged into a pynigma cipher. So:

1

2

3

4

5

6

APEAPEAPEAPEAPE <-- repeated key

===============

BJIPOSFO1FUJLAZ <-- resulting ciphertext from PyNigma

XOR the above with your plaintext of "ATTACK AT DAWN" to obtain a ciphertext!

Could be onto something there!